ARC Celebrates Black History

Throughout my first six months here at ARC I have found that my Blackness is valued even if it’s not understood. During this Black History Month, I found myself in a point of reflection relating to the past contributions, present state, and future possibilities for Black bodies in space. Being the only Black woman displaced from African decent at ARC, my design methodology for curating this month-long celebration was centered around the adaption to eraser, and creolization.

I was first introduced to architecture when I was in the eighth grade participating in a Washington DC design program called City Vision. At this time, there were approximately 196 Black women architects who were licensed in the U.S. This statistic meant that my first encounters with architects were with people who did not resemble me. This did not concern me at that time, but I have come to see things differently in my pursuit of my Master of Architecture degree at Rhode Island School of Design.

After my initial introduction to architecture in middle school, I continued this pursuit attending Phelps Architecture Construction and Engineering High School. Although much of my high school cohort was African American, we were only introduced to one Black woman practicing architecture in our time there. It wouldn’t be until my first year of graduate school at RISD that I would meet another Black woman practicing architecture, and that has made a difference in how I value representation in education. Throughout my 14-year education, I have been introduced to no more than ten licensed Black architects, two of which were Black woman. Furthermore the conscious effort to erase Black architects contributions has been prevalent in academia: I was not taught about Black architects in high school, undergrad or graduate school.

Blackness regarding architecture is universal. The universality of Blackness is a reality that is inherently problematic. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie defines it as “The danger of a single story.” She states “the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.” (Adichie, 2007). A single story produces a dominant narrative and prescriptive modes of representation. Although the stories happen at multiple scales across the world, people who share this melanin skin experience racial profiling.

I framed the Black History Month celebration in the attempt to decompose the single narrative of Black people through architecture. It was important for me to both celebrate Black architects, and also hold the profession accountable for its inherent lack of care or effort to bridge the racial gap in architecture.

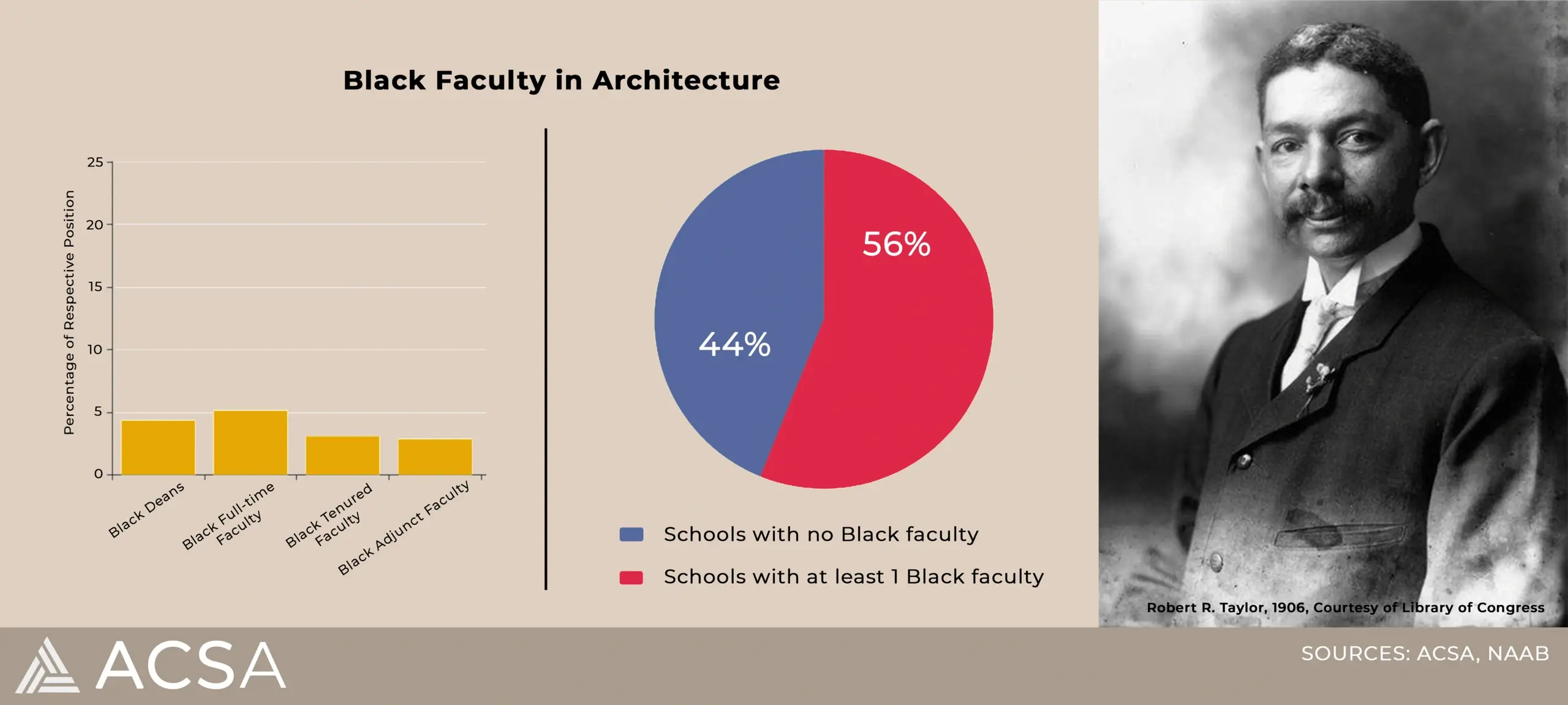

We started the month out by highlighting Robert R. Taylor, the first Black architect. What I found most inspirational was learning that Taylor was educated in Copley Square where ARC is located. Taylor was pivotal in shaping the education for future Black architect as he helped create the first Architecture Departments at Tuskegee University, one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

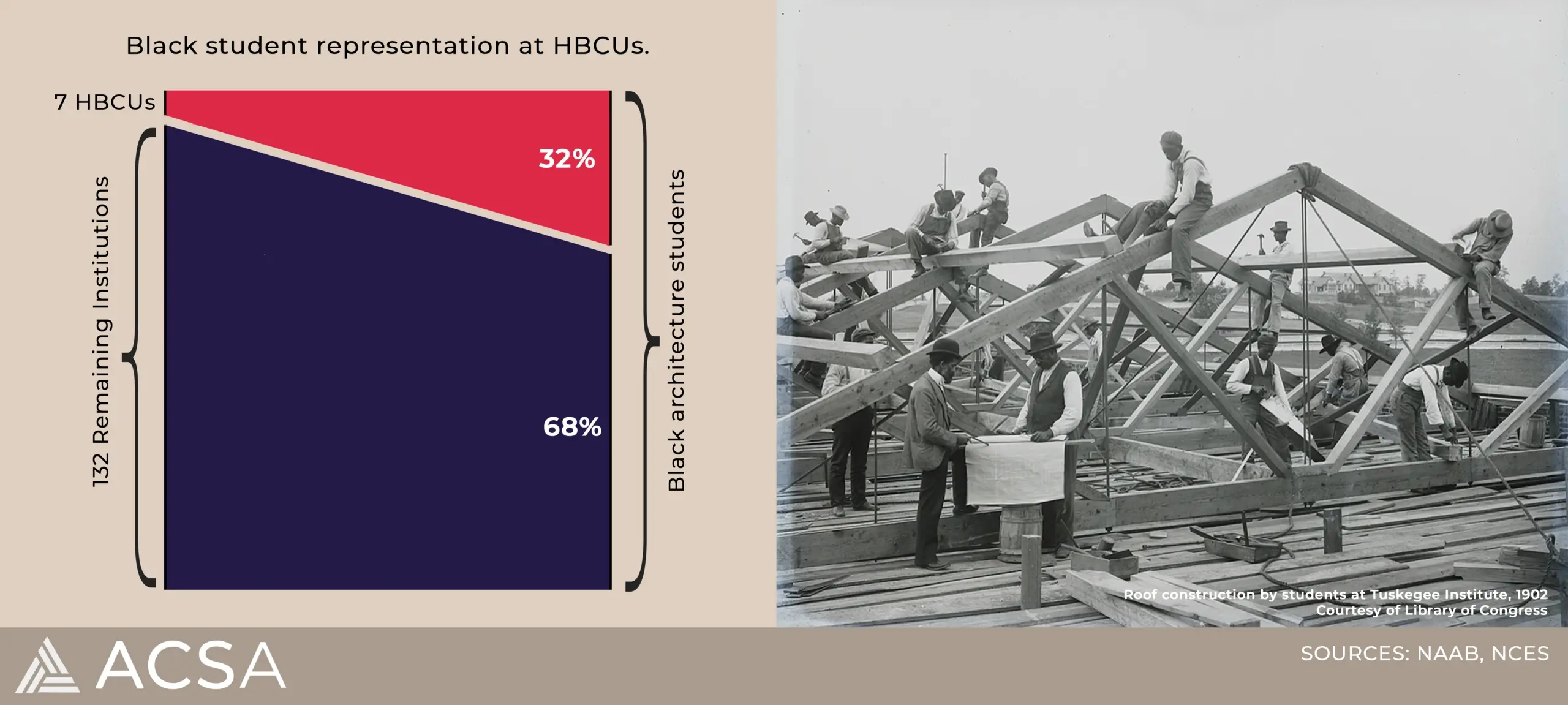

Being an alumnus of the illustrious Morgan State University, it was important for me to highlight the institutions that educate Black architects. HBCUs are excluded from the rankings of Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) forcing them to compete amongst one another, and severely limiting their exposure and well-deserved recognition. It prides me to say that I work at a firm that wants to hire from HBCUs and recognizes the role of HBCUs in bridging the racial gap in architecture.

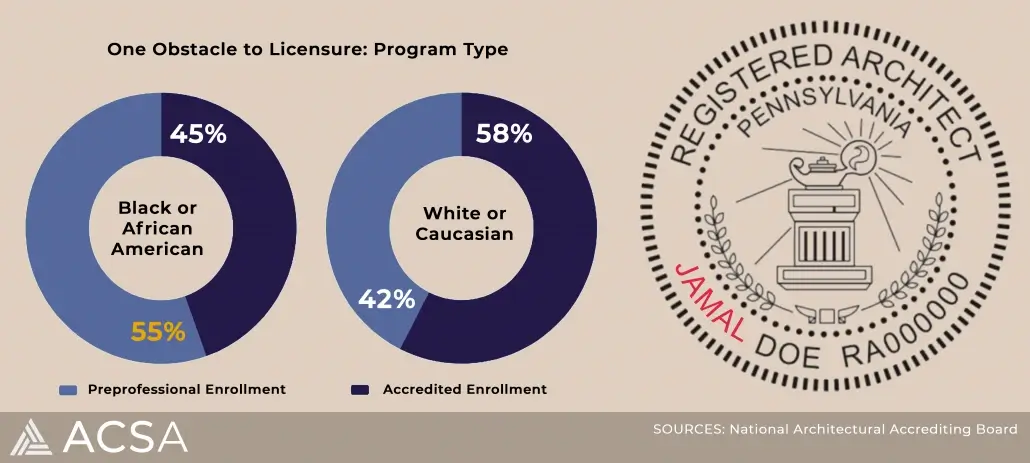

I found that pointing out the disparity of Black students studying architecture to the number of Black architects was important to truly understand why there are only two percent licensed Black architects in America. It is known that Black people pursuing licensure are at disadvantage. The architecture profession is just now attempting to address this issue with scholarship and programs to support Black people.

“Representation equals success.” Jackey Robinson

In 2021, MOMA featured an exhibition curated by Black architects titled "Reconstructions Architecture and Blackness in America." This was the first time that Blackness has been acknowledged as being a form of architectural representation. The collection of architects speaks to the creolization of Blackness in America.

This journey has been informative, liberating and motivational, and I want to give props to ARC for being open and trusting. The Architecture profession and ARC have a lot of work to do in progressing their efforts in representation and diversity. This is a great catalyst of the possibilities that lie ahead.

Unapologetically,

Teisha Bradley